Rural Utopias Residency: Alana Hunt in Kununurra #3

Alana Hunt is currently working with the community of Kununurra. This residency forms part of one of Spaced’s current programs, Rural Utopias.

Alana Hunt is an artist and writer who lives on Miriwoong country in the north-west of Australia. This and her long-standing relationship with South Asia—and with Kashmir in particular—shapes her engagement with the violence that results from the fragility of nations and the aspirations and failures of colonial dreams.

Here, Alana shares an update from Kununurra.

In the days before Christmas, in late 2021, I flew from Kununurra to Perth in order to record Sam Walsh AO narrate for over 2 hours and 41 minutes, without pause. He read aloud the project summaries of 967 Section 18 applications made in Western Australia since 2010. Each application sought permission from the Minister responsible for the Aboriginal Heritage Act in the WA State government to “destroy, damage or alter an Aboriginal site”. I sourced this material from publicly available records online, that only date back to 2010. However, since the legislation came into effect in 1972, it is estimated over 3300 applications have been processed. Only three have ever been declined. Under the guise of protecting Aboriginal heritage this legislation opens a pathway for its destruction.

Throughout his 25 year career with the international mining group Rio Tinto—culminating in his appointment as CEO between 2013-16—Sam would have been party to any number of these applications. He was indeed CEO at the time the WA government granted Rio Tinto permission for the “development of the Brockman 4 mine” which resulted in the blasting of two rock shelters at Juukan Gorge—an event which brought WA’s Aboriginal Heritage Act into the public sphere. More recently, Sam has spoken publicly about issuing a verbal instruction that Juukan Gorge was not to be mined when he found out Rio Tinto had been granted the Section 18 and this held for seven years until after his retirement. He also spoke of the need for major reform for industry and legislation. He expressed serious concern the WA government’s recent amendments to the Aboriginal Heritage Act, passed in the week before Sam and I met, still give government and industry more power than First Nations people.

And so—following my direction to a tee—in the dim quiet of a recording studio in Perth, Sam read aloud. His narration was diligent and calm and consistent. Again. And again. And again. And again. There is an assuredness to his voice, that could, at one level, obscure the violence he describes. Yet, perhaps it is precisely that self-assured timbre of his voice—like the banality of the Arial font in the video, pulled from a government pdf—that also acts to accentuate the fact of violence. A specific kind of violence, birthed through bureaucratic processes that appear clean on paper, but wreak havoc in the world.

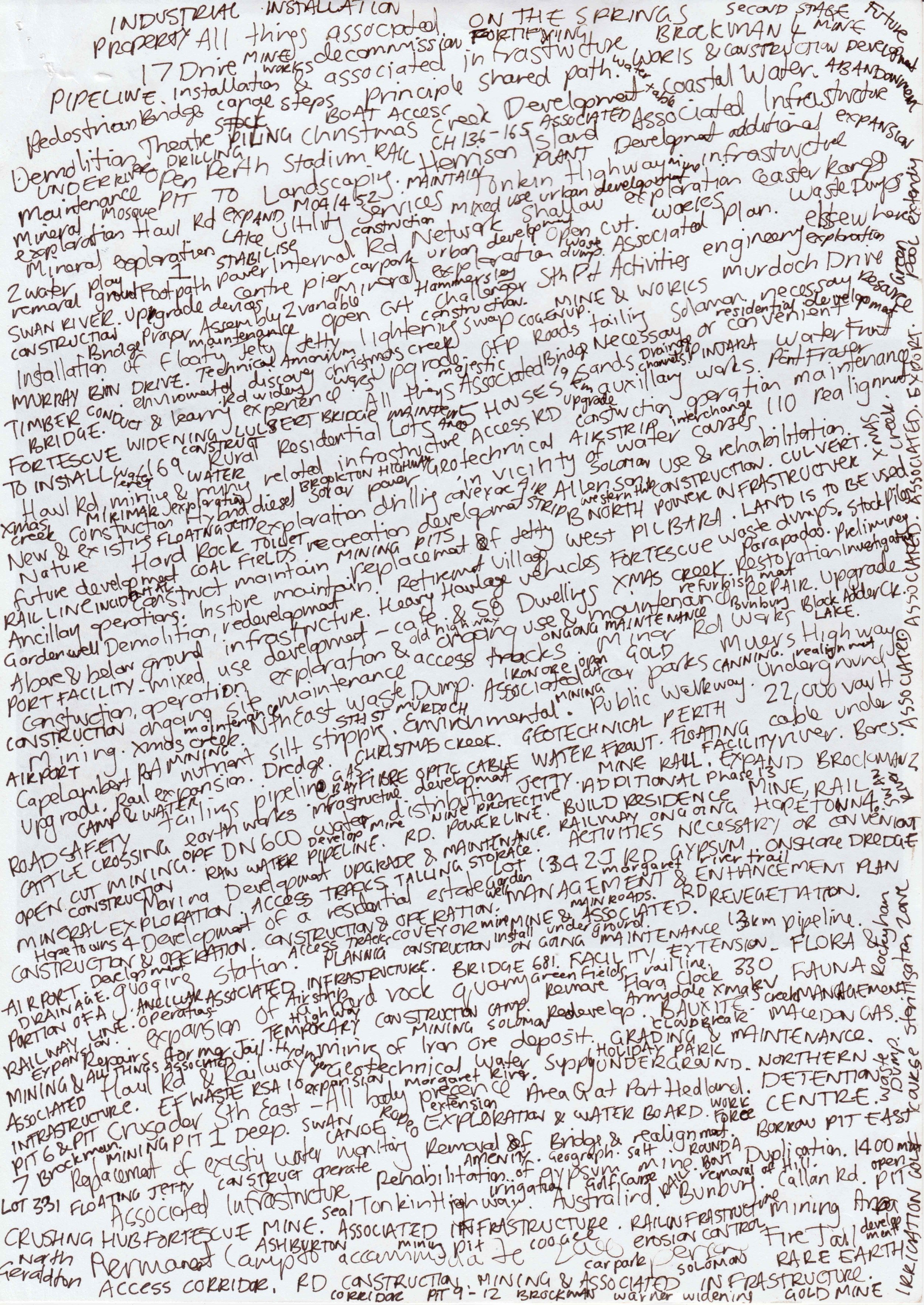

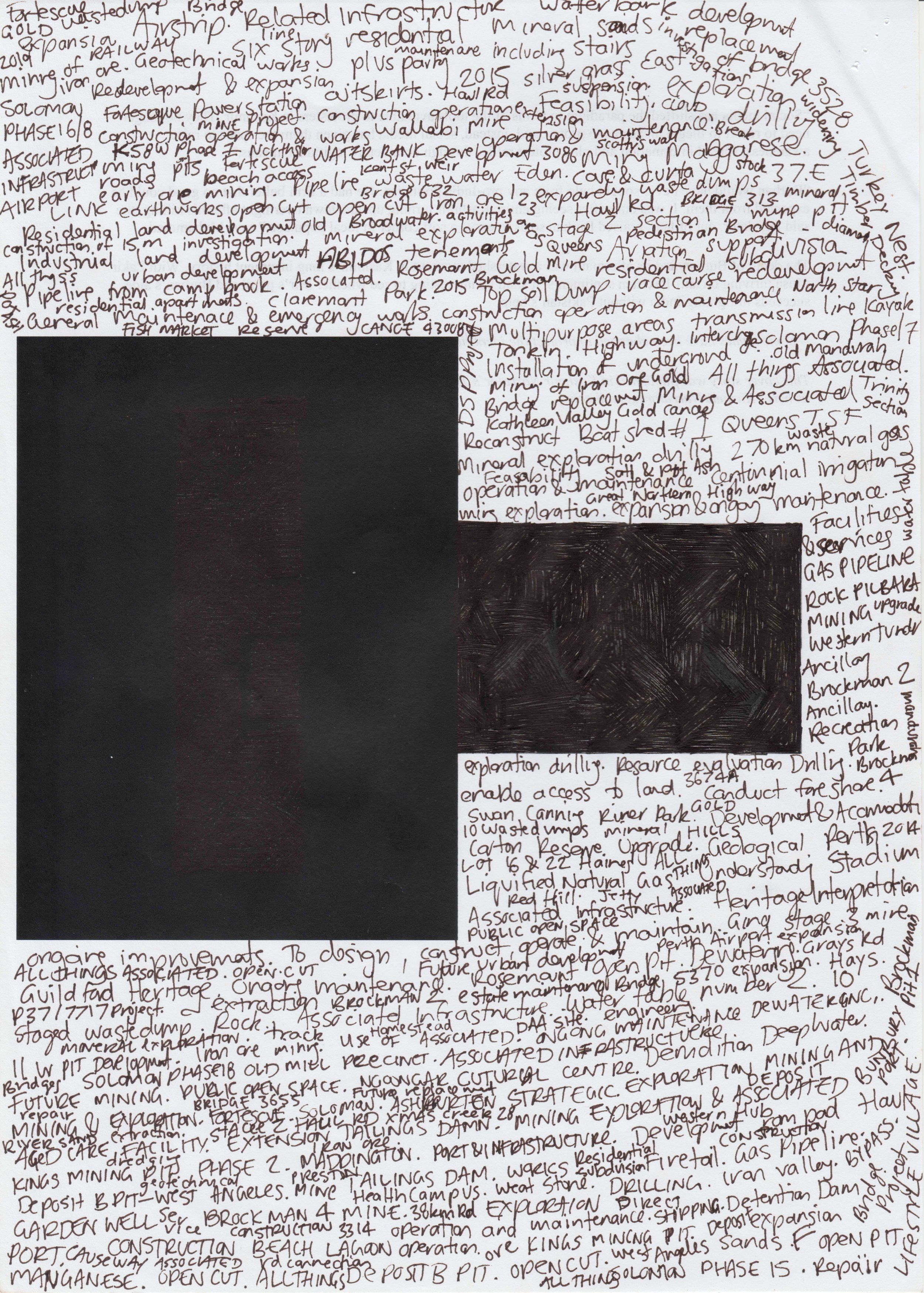

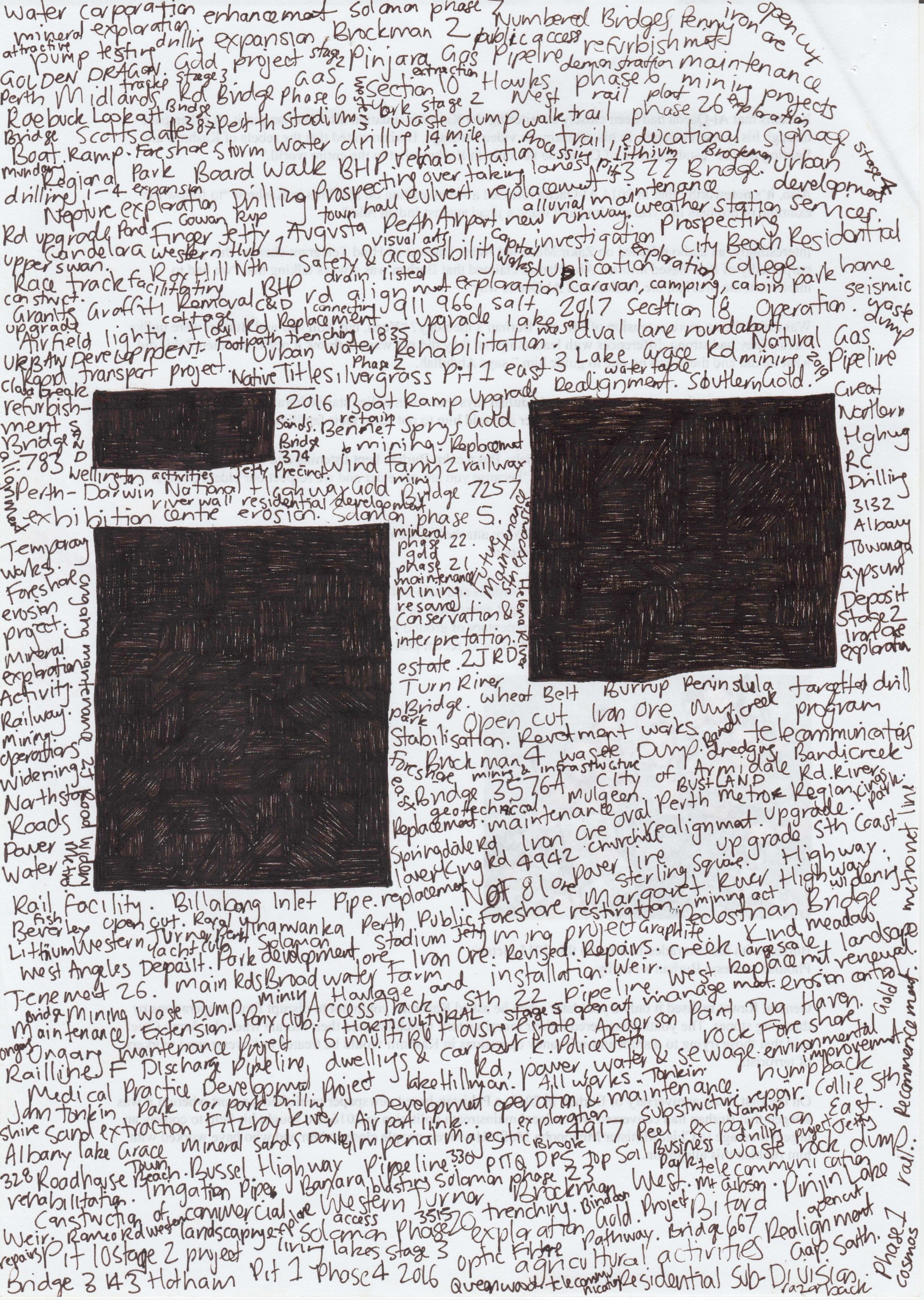

While Sam read, I wrote. Intuitively. I started trying to capture a word or phrase from every project summary he read. It wasn’t something I planned, but more something I started doing to keep focus. Sam had asked me to stay in the room with him while he narrated, in case there was an error we needed to work through. I had to keep very quiet, and suddenly found myself balancing with the papers resting awkwardly on my knee. My writing came to fill three scraps of A4 paper I happened to have at hand—they contained, on one side an article by Asif Sultan, a Kashmiri journalist detained in prison since August 2018. And on the other side draft design layouts for another work Cups of nun chai. Such is the collision of an art practice.

To me these hastily scribbled notes, and the video Sam’s narration accompanies, paint a very clear picture of colonisation in Western Australia (of empire, of capital, of development) and how everything from large scale mines to seemingly innocuous things like footpaths, jetties and housing estates play a part in this process. As we all do. This is not colonial violence of some distant past, but here and now. And it confronts the fact that every inch of this continent is Aboriginal land.

In the week before Sam and I recorded, the WA Government passed new legislation it claimed would modernise the Aboriginal Heritage Act (1972), bringing it up to more “progressive” standards. But the new legislation contains many of the same fault lines that ran through the old one. Perpetuating a situation where one continues to seek legal permission to undertake what is otherwise recognised as a crime. In an unprecedented move, a United Nations committee has intervened, raising concerns the new legislation in WA will maintain the structural racism of the Act[1]. Tyronne Garstone, CEO of the Kimberley Land Council stated: “The McGowan Government has wasted an opportunity to create legislation that strikes a balance between development and heritage protection. This Bill continues to expose Aboriginal heritage to destruction and disempowers Traditional Owners to speak for their country. In a state where the economy is driven by the mining and resource sector, once again, the needs of industry trump everyone else.”

So, within this nexus of industry, government and life, I’m thinking now about how to share this video with the world—where to circulate? And how? A possible screening in the picture garden in Kununurra? A billboard in Perth? A 967 page ring bound folder, delivered to every MP who voted on the new legislation with the accompanying audio? A slow-tv broadcast? Or perhaps better yet a screening on a privately chartered flight to a mine site? A pirate TV / radio intervention, that interrupts the evening news? Or could it play, as a friend suggested, on loop in every single regional airport in WA—replacing the tourism ads for pearling, pubs and pristine landscapes. Imagine a giant spread of wallpaper as a mournful kind of monument inside the WA Parliament, or the Minister for Indigenous Affairs offices?

[1] https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2021/12/10/un-committee-raises-concerns-over-new-heritage-laws-1